A Tribe Under Siege: The Ongoing Indigenous Genocide in Bergen County’s Backyard

February 12, 2024

By Griffin Asnis

Griffin Asnis was a Fall 2023 intern at the Puffin Cultural Forum. The following blog post was written and submitted as a part of Griffin’s Capstone Project, which is designed so that interns have the opportunity to research and execute a project based on a topic they are passionate about. They are completed at the conclusion of the internship.

For thousands of years, the Lenape people have called the Mid-Atlantic region home. Seeking refuge from colonial violence over 300 years ago, the Ramapough Lunaape Nation—a Munsee-speaking band of the Lenape—established an enduring community in the foothills of the Ramapo Mountains. After centuries characterized by displacement, dispossession, and systematic extermination, between 1,000 and 3,000 tribal members remain in the areas we know as Rockland County in New York and Bergen, Passaic, and Sussex counties in New Jersey.

Yet, despite the passage of time since the Ramapough’s initial contact with European colonizers, the genocide of our Indigenous neighbors continues in insidious forms. This genocide is rooted primarily in the federal government’s refusal to acknowledge the Ramapough’s tribal identity, consequently depriving them of necessary social services and economic benefits, facilitating the destruction of their land and food sources, and eroding their cultural identity as a distinct people. The Ramapough’s perennial struggle for self-determination is ultimately indicative of the incompatibility of justice for Indigenous peoples with our legal system. As a result, in our capacity as private citizens—and beneficiaries of stolen lands—we must leverage our own resources to aid the Ramapough in their active resistance against a system erasing their very existence.

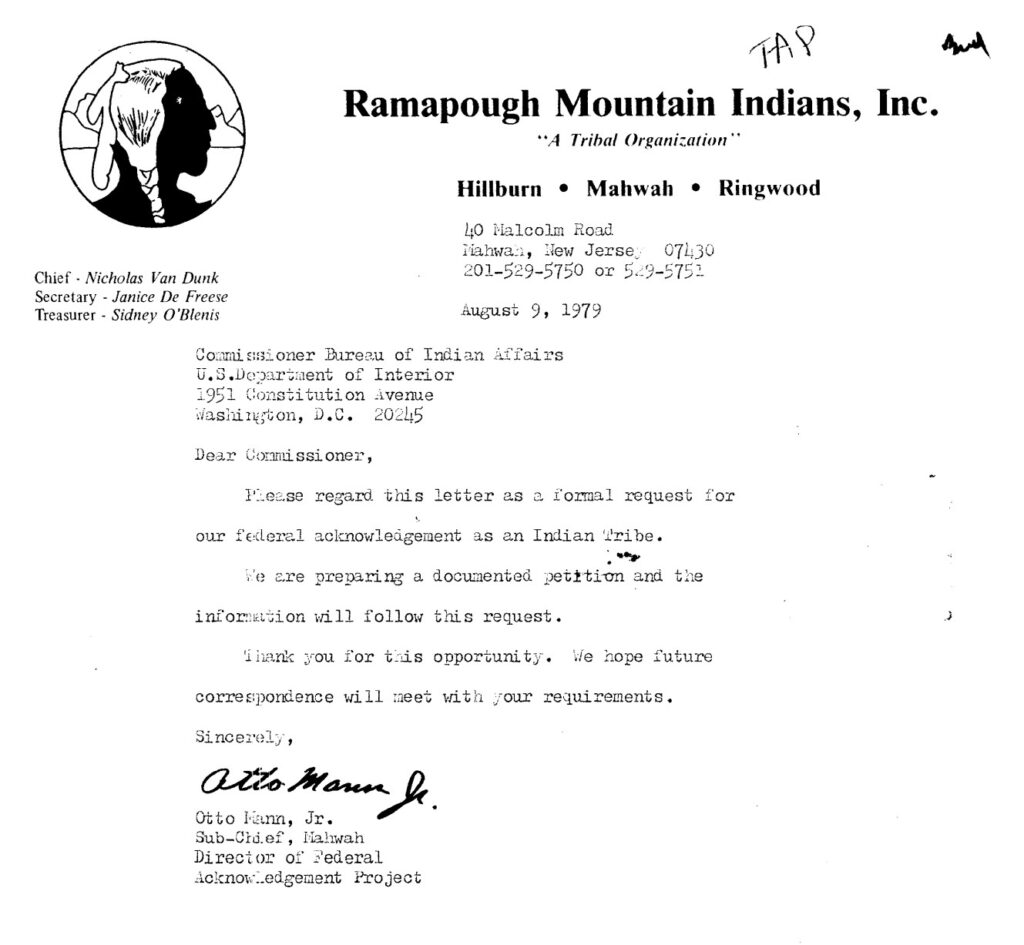

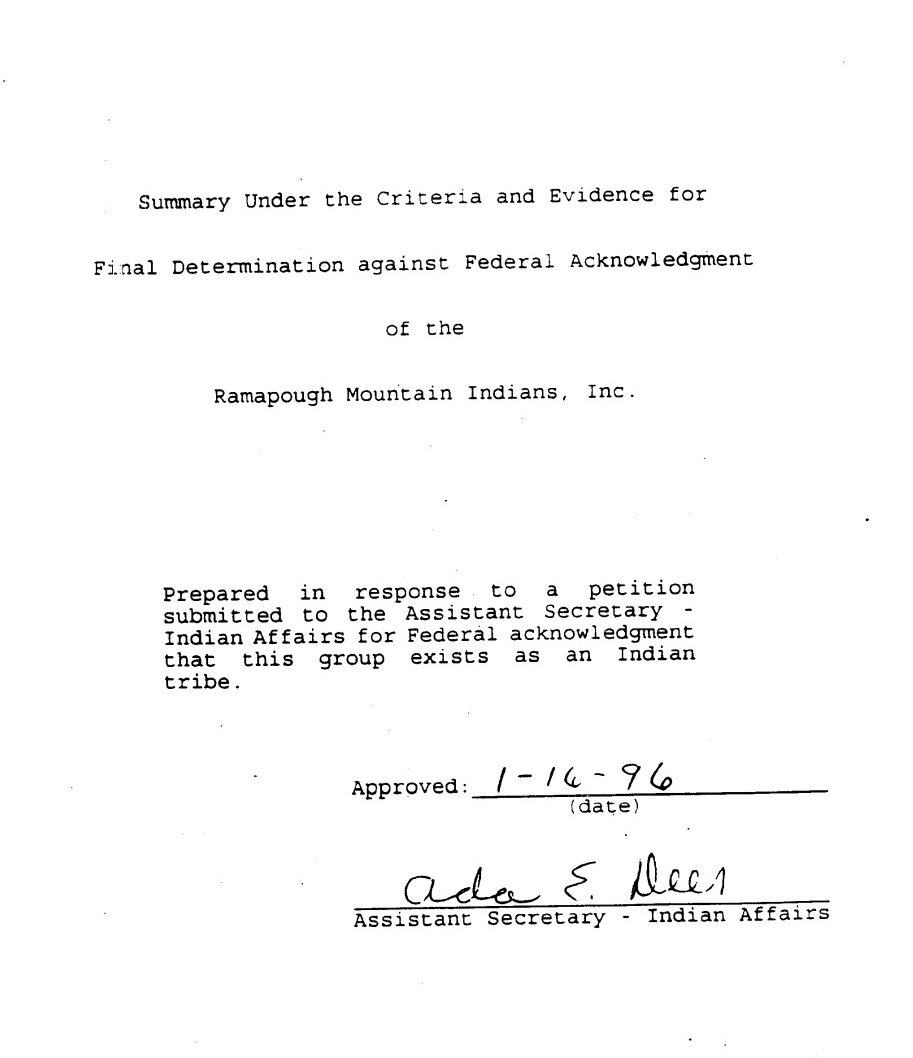

Central to the tribe’s fight for self-determination is a continued quest for federal recognition. This designation establishes a “government-to-government” relationship between an Indigenous tribal government and the U.S. government, which affords a tribe the right to self-governance, among other privileges, protections, and benefits otherwise out of reach for non-federally recognized tribes. Though it is supposed to serve as a vehicle for justice, federal recognition is largely inaccessible in practice, as the U.S. government prioritizes disqualification over rectification. Both costly and time-intensive, the Federal Acknowledgment Process (FAP) inundates petitioning groups with paperwork and myriad prerequisites, amounting to “administrative genocide.”

A petitioner must demonstrate substantial continuity of existence since 1900—no small feat for Indigenous peoples, who often lack written histories due to an intergenerational reliance on oral storytelling traditions. Furthermore, the government’s historical practices of tribal document destruction and forced assimilation, coupled with the extermination of Indigenous populations, necessarily destroy the petitioners’ ability to meet such criteria in the first place.

The requirement of descent from a historical tribe similarly proves problematic, relying on an archaic construct of race that negates the complexities of Indigenous identity while overemphasizing a misleading notion of racial purity. In their pursuit of federal recognition, tribes must contend with a colonial framework that weaponizes their multiracial ancestries against them. The Ramapough’s assertions of Indigeneity are consistently met with the skepticism of the surrounding white population and the government alike, stemming in part from a simplistic census classification system that remained in effect until 1870 in New Jersey. The state would classify its residents “only as white, black free or black slave,” giving way to pernicious folk legends and unsubstantiated claims regarding the tribe’s origins. In essence, white conceptions of Indigeneity rendered Native Americans invisible in historical records. The FAP’s criteria of continuous existence and tribal descent in their current form therefore remain thoroughly unjust.

While federal non-recognition delegitimizes the tribal identity and history of the Ramapough people, its implications are not merely symbolic in nature—they are material, too; federal non-recognition deprives the Ramapough of necessary social services and economic benefits critical to their survival. These resources, managed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and distributed to federally recognized tribes, include financial loans, job training, land allotments, child care, and healthcare access via reservation-based clinics and hospitals. Inadvertently, the FAP has created a caste system in which federally recognized tribes are accorded such resources, while unrecognized tribes are left to fend for themselves. The COVID-19 pandemic only amplified this existing dichotomy; over 200 non-federally recognized tribes acutely felt the impacts of their so-called illegitimate status when they were excluded from a vital $31 billion federal aid package, as well as vaccine allocations and testing supplies, reserved only for federally recognized tribes.

Additionally, despite their proximity to wealthy suburbs, the Ramapough battle a high poverty rate and an ever-rising cost of living, often subject to overcrowded living conditions. Potential major sources of revenue such as casinos remain out of reach for the Ramapough, who are subject to state laws and thereby not entitled to establish gaming operations, unlike their recognized counterparts. Thus, the Ramapough have relatively little hope for large-scale economic development in the foreseeable future, lacking a means by which they can provide for their community in the absence of federal recognition.

Beyond depriving the Ramapough of crucial social services and economic benefits, federal non-recognition denies tribal members land sovereignty, enabling the ongoing destruction of their homes and food sources by corporate greed. The Ramapough Lunaape Turtle Clan suffers the persistent impacts of Ford Motor Company’s indiscriminate dumping during the 1960s and ’70s in Upper Ringwood, New Jersey. Originally designated by the Environmental Protection Agency as a Superfund site in 1983 and relisted as such in 2006, the abandoned iron mining site is riddled with lead, arsenic, and 1,4-dioxane.

A New York University study conducted between 2015 and 2016 found a “significant association” between self-reported exposure to the Superfund site and incidents of bronchitis, as well as elevated levels of asthma, heart disease, and high blood pressure among those who reported “multiple interactions” with the Superfund site. Strikingly, the Ramapough were 13.84 times more likely to face exposure to the site as compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts in Ringwood. While over 53,000 tons of paint sludge and soil have been removed from the location since 2004, the drawn-out remediation effort is perceived as wholly inadequate by local tribal members, who have been forced to relocate en masse and have seen countless community members lost to deadly cancers. Tribal members even allude to one particular residential street, Van Dunk Lane, as “Cancer Row”—a reference to the disease’s impact on nearly every household on the street.

Toxic dumping has also poisoned the community’s food sources. Hunting, fishing, planting, and gathering are integral to the Ramapough’s way of life, but toxic waste continues to degrade their surrounding environment—tribal members have even encountered bubbling tumors inside the bodies of hunted deer. No element of Upper Ringwood’s ecosystem has been spared from the impacts of corporate malfeasance enabled by federal non-recognition.

On the left: EPA-led remediation work in progress at the Superfund site in Ringwood, NJ. Source: Michael Sol Warren/NJ Spotlight News

On the right: Ringwood dump site marked by an EPA warning sign. Source: Al Jazeera

Perhaps the most insidious manifestation of the ongoing genocide is cultural destruction. Without federal recognition, the Ramapough are not entitled to a reservation, preventing tribal members from living communally. The resulting dispersal of members across the region inherently increases the difficulty of cultural preservation. Restrictive zoning ordinances further interfere with the group’s cultural practices via a de facto ban on religious structures. In 2016, the Ramapough established the Split Rock Sweetwater Prayer Camp, which included the erection of tepees on their property off Halifax Road in Mahwah, New Jersey, in protest of a proposed oil pipeline that would dissect tribal land.

Despite the Ramapough’s centuries-long use of the site for religious and communal purposes, the group faced excessive fines from the township and over 100 summonses for failure to secure zoning permits for its tepees, prompted by noise complaints from the surrounding private community. In response, the tribe asserted its constitutional rights, including its right to religious freedom. Nevertheless, a Superior Court judge ultimately sided with the township, upholding a 2017 ruling which authorized the summonses issued against the tribe. Such punitive measures target the Ramapough’s very essence by stifling cultural expression and perpetuating the erasure of Ramapough culture. Indeed, cultural destruction constitutes an “integral part of genocide,” which threatens the vitality of the group itself, not just the lives of its individuals.

In the face of quiet genocide, the Ramapough are not passive subjects, however—they have united to provide for themselves and to reclaim their traditional lifestyle. The Munsee Three Sisters Medicinal Farm in Newton, New Jersey, epitomizes the Ramapough’s collective resilience and their innovative approach to communal healing. Co-founded by Turtle Clan Chief Vincent Mann and Clan Mother Michaeline Picaro in 2019, the for-profit farm creates employment opportunities for the Ramapough while generating revenue via the sale of crops, personal care products, and Native crafts. Through sustainable agriculture, the farm also provides nutritional foods at no cost to tribal members in need. Permitting members to harvest crops free from contamination in a protected communal space, the 14-acre farm fosters the rebuilding of an endangered Ramapough culture. More than a means of sustenance, this enterprise embodies a form of potent resistance through which the Ramapough people are recovering sovereignty on their own terms.

Nevertheless, as non-Indigenous community members living on the tribe’s ancestral lands, North Jersey residents play a crucial role in this ongoing narrative, too. In light of the federal government’s continued negligence, we must turn to civic action to help ensure the survival of the Ramapough people. The tribe’s recent reclamation of Split Rock Mountain (Tahetaweew) along the New York-New Jersey border provides a compelling example of cross-community collaboration and a model for future action: Thanks to $500,000 in private donations, The Land Conservancy of New Jersey purchased the sacred site from Rockland County, transferring the deed back to the Ramapough for the first time since the eighteenth century.

Marking a years-long effort, the exchange involved various community stakeholders, including the Mahwah Environmental Volunteers Organization, the Ramapo Munsee Land Alliance, and over 50 private donors. Split Rock Mountain’s return to the Ramapough is indeed illustrative of the significant impact non-Indigenous community members make when they harness their own resources in the service of justice.

Justice for the Ramapough people requires that we prioritize their input about their own needs by directly engaging with tribal members and Indigenous-led organizations. The tribe offers a wealth of opportunities for non-Indigenous allies to form meaningful relationships with individual members, including film screenings and lectures, craft fairs, interfaith celebrations, and solidarity walks; such events are frequently featured on the tribe’s Split Rock Sweetwater Prayer Camp and Ramapough Community Center Facebook pages. Of course, financial support in the form of donations, however big or small, to nonprofit organizations like the Ramapough Culture and Land Foundation and the Sweetwater Cultural Center is key to covering operational costs and fulfilling their mission to uplift the Ramapough community. Supporting Ramapough-owned businesses, especially the tribe’s medicinal farm (which also welcomes volunteer support), is similarly essential. Yet meaningful contributions can also be derived from our own interpersonal relationships as well as our labor—such as leveraging personal and professional connections to heighten awareness of the tribe’s pressing needs, forming organizational partnerships, amplifying the Ramapough’s calls for federal recognition, and recruiting and joining volunteers to participate in community projects like environmental clean-up efforts on Ramapough land. Given the federal government’s inaction and the tribe’s unanswered appeals for justice through our legal system, our own contributions are paramount to the survival of the Ramapough people. After all, the law will not resolve the Ramapough’s existential struggle because it is the very mechanism by which this genocide is perpetuated.